Last week we ran the first half of a two-hour interview I did with Emmis CEO Jeff Smulyan and Rick Cummings, Emmis President of Programming.

It’s remarkable to have a CEO agree to a 30-minute interview. Two hours is unheard of, but this was a unique circumstance. Jeff has permitted me to say he was isolated over a holiday weekend last Summer. I’m sure most people he knows were spending quality time with their families because each time I offered to wrap up the discussion, Jeff insisted he was having fun and said to keep going. That is what Rick Cumming probably had planned, but he is a good sport and hung in the entire two hours. Rick’s presence is a bonus you usually don’t get in an interview with Smulyan.

A transcript of a two-hour interview with such an accomplished CEO as Jeff Smulyan and a programmer as Rick Cummings is unheard of, perhaps unprecedented.

It’s only been edited for clarity. It’s lengthy but covers so many topics that it’s worth the time investment. A long holiday weekend maybe just the time to catch up on some reading

Since I’ve mentioned the holiday weekend, I want to thank each of you who have been reading the columns that I’ve written for Barrett Media since the start of the Summer. I appreciate your time investment and your comments – regardless of whether you agree or disagree with me. I always enjoy hearing your thoughts. You can reach me on Twitter @AndyBloomCom or by email andy@andybloom.com.

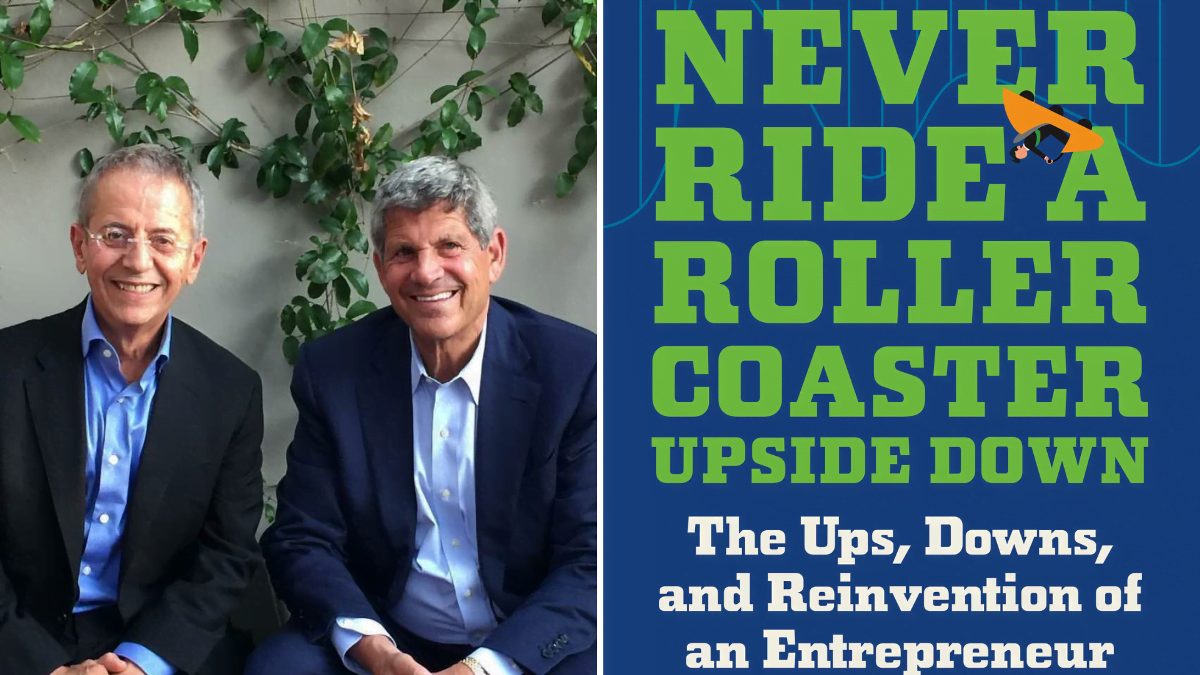

I find Jeff: smart, funny, insightful, and, like the name of his company, honest. If you do, too, consider getting Jeff’s book: “Never Ride a Rollercoaster Upside Down: The Ups, Downs, and Reinvention of an Entrepreneur,” which will be released on December 6th.

Part one covers Smulyan’s discovery of radio while growing up in Indianapolis. His passion for baseball, apparent at a young age, college and why he went to law school but doesn’t practice. Stories about the beginning of his radio career, including David Letterman and how his relationship with Cummings begins, which you don’t want to skip, and how he won another station’s major contest. It includes his experience owning a Major League Baseball team, how NextRadio began Emmis’ exit from radio, and the reasons why.

If you didn’t read part one, it’s available here:

Here is part two of the Jeff Smulyan interview with special guest Rick Cummings:

Andy: Your experiences help clarify why you exited the business.

Jeff: Andy, writing the book gave me a chance to look year-by-year at the business. When you look at the growth of radio, the decline started in 2001. The Wall Street love affair with radio began in 96. Before then, the industry grew 4 to 7% a year. From 96 to 2001 it probably grew 7 to 9% a year. Then came the dot com bubble. From 2001 to 2009, it limped along at maybe 2 or 3%. Then it declined by 25 or 30% from 09 to 11 with the recession. The industry peaked at, I think, $21 billion a year. And then I think it dropped from $21 billion to $17 billion in 2009. Then from 2011 until COVID, it stayed at 16 to 17 billion, but the character changed, and there was a lot more NTR and digital. The over-the-air spot stuff, which was always the high-profit stuff, is only about 13 billion. Then COVID hit, and the whole thing dropped from 17 to 14 billion. It’s coming back now, probably to 16, but the nature of it, the profitability, the margins, it’s all changed. You look at the industry map and can see why it is where it is. I’m doing this off the top of my head, but I’m close.

Jeff: Andy, writing the book gave me a chance to look year by year at the business. When you look at the growth of radio, the decline started in 2001. We had the dot com bubble and the Wall Street love affair with radio that began in 96. For five years, the industry grew. This industry before that grew 4 to 7% a year. From 96 to 2001 it probably grew 7 to 9% a year. Then it stopped. If you look at this business from 2001 to today, 20 years later. It limped along, maybe two or three percent from 2001 to 2009. Then it declined by 25 or 30% from 09 to 11 with the recession. Then it lost – the industry peaked at, I think, $21 billion a year. And then I think it dropped from $21 billion to $17 billion in 2009. I’m doing this off the top of my head, but I’m close. Then from 2011 until COVID, it stayed at 16 to 17 billion, but the character changed, and there was a lot more NTR and digital. The over-the-air spot stuff, which was always the high-profit stuff, is only about 13 billion. Then COVID hit, and the whole thing dropped from 17 to 14 billion. It’s coming back now, probably to 16, but the nature of it, the profitability, the margins, it’s all changed. You look at the industry map and can see why it is where it is.

Rick: All of this happened in the context of Facebook now doing 60 billion a year.

Jeff: Yeah, all the local revenue went elsewhere. Facebook and Google and you’re competing with other ecosystems. You could just see the steady decline.

Rick: I would add another thing that occurred in the last ten years. One of the things that was so fun about the business was that we were the gatekeepers of music distribution and discovery. Probably, starting ten years ago, I began to notice with my kids and then everybody else’s that they weren’t listening to the radio. In the last five years, the TikToks of the world have become the music discovery vehicles. When Jacobs’ TechSurvey shows, basically, these are all radio people (listeners) they survey, and it shows that they can’t find anybody under the age of 35, that’s pretty deflating. That was one of the things that made this so much fun: breaking hit records and having the younger end of the demographics really engage with your products, and those days are gone.

Jeff: When I went to school, KHJ debuted in L.A. You couldn’t be in your car at an intersection without hearing it. When we put Power on the air In 1986, you couldn’t go down the street without hearing Power on the air. Today people still listen to the radio in their cars, but the impact on people’s lives is just gone.

Andy: You mentioned portability. The first clue I had, to use your phrase, that radio was about to receive the death knell was the loss of the nightstand. When the industry lost the nightstand, when clock radios disappeared, and iPhones took their place, I thought radio was in real trouble. That happened and should have been a wake-up call. The last frontier for this industry is the car. The dashboard is in the process of changing. You are now in a position where you can say anything you want. You don’t have to show up at those NAB or RAB meetings.

Jeff: Right. You know, those are the people that have been my friends for 50 years. You know that?

Andy: I do know that. But maybe you can speak more freely, or perhaps you’d say the same thing regardless of your position. But the dashboard is certainly the last frontier. Right? What advice to the industry do you have to protect the dashboard?

Jeff: It is the advice that I had with NextRadio. The minute we launched it, Ford came to us and said, this is your future. What you built for smartphones, we want to put in dashboards. Now, the problem was there were some pretty interesting reactions against that by some of our peers who shall remain nameless. You can figure out who really didn’t want an industry effort there for their own purposes. It’s very clear that, and again I’m going to save this for the book because when you read the whole story, it’s hilarious. It was very clear that we had to have interactive radio in the dashboard. To an extent, I think that’s what they’re doing. I think iBiquity is doing it, and they’ve taken on a lot of the stuff we did. Obviously, you had to have that. It was clear, Andy, This is one of the reasons we vacated the space because there’s probably going to be a steady erosion because it’s tougher. You get in a car today, and it has Apple CarPlay. It takes you three switches to hit the terrestrial signal.

Rick: Radio is going to have to evolve much more to spoken word and personalities, which is a tremendous hurdle when you consider what most of the big groups have done over the last 15 years, which is to voice track things and pipe things in from out of the market. The only thing radio can offer these days that is unique is personality because music delivery as a linear system is really fading fast. I think that’s going to be a very challenging hurdle. But I think the industry will survive. The industry will have to evolve much more into spoken word and personalities in local communities if it is going to remain relevant.

Jeff: That’s why the Bud Waters of the world will tell you that they have remained local and live and are more relatable to their communities. Frankly, they like competing with the big three groups that are sending (content) down the pipe and don’t even have a market manager in those places.

Andy: Let’s talk about the book, being released on December 6. Your daughter suggested you needed to write a book. Let’s start with the process. How does Jeff Smulyan write a book?

Jeff: At heart, I’ve always been a writer. I spent three summers at the Indianapolis Star. When I was bored doing religious radio, I wrote a book called The Emmis Region; that’s how the company got its name. When I got out of baseball, I wrote 800 pages about my experiences in Seattle. I have always liked writing. When Covid started, and things were slow, I just sat at my desk, and 45 days later, I had 300 pages. I sent it to a couple of friends. My nephew, my niece’s husband, is an agent and now has a production company. I said, do me a favor; read it. He said, look, you really have something. Jill Greenthal, a friend and a former Emmis investment banker, said, send it to me. She read it, and she said, you’ve got something here. She said, my husband, teaches at Harvard. He just published a book. His editor is one of the great people of all time.

You need somebody independent to look at it, tighten it up, and make suggestions. She said, here’s the template; you and the editor will come up with a presentation. You’ll do two sample chapters that you’ve cleaned up. You put an outline together with an overview of the book, and you send it off to some agents. Hopefully, you’ll get an agent, and hopefully, the agent will find a publisher. That’s what happened. My agent found a boutique publisher, Matt Holt, that distributes through Random House. I love the guy. We signed with him last fall. It took me about a year to go through the process.

Do I really want to do this? Do I not? It took me six months to sign up the editor after I’d written it. Writing, the book was cathartic. Then working with the editor, Phyllis Strong, who is just terrific. She would say, “Okay, you’ve written this; now elaborate on that, or hey, this is extraneous; it doesn’t move the story along.” The next thing I knew, we had a publisher, and they did their edits. Now the book is finally done. They said we can rush everything and get it out for the spring, but we think you ought to take your time. We’ll get it out for the fall. That’s the best bookselling season. I have no idea if anybody will like it. I got my first review, which was very positive, from Kirkus Reviews. I know that I’ve had more fun with it than anything I’ve ever done.

Andy: It wasn’t difficult?

Jeff: Every step of the process was fun; let me put it that way. The actual writing was easy because I just wrote what I thought. The editing was fun because I had a dispassionate editor who could say, “I like this, but add to this or cut this.” We’d go back and forth and tighten things up. She’s a great partner. The gratifying thing is people say, yeah, you write well, and you write funny. Who knows if that’s true or not? But that was gratifying. There have been some gratifying moments. I’m sure I’m going to have ungratifying moments.

The publisher had a copy editor, who I kid is the wizard of colons and semicolons. Everything’s got to be the right style, and he was great. He got done, and he sent me a note, saying, I love this book. I called him and said, oh, you must say that to all the girls. He said, I’ve been doing this for 40 years, and I’m telling you, I don’t like much, but I love this book. I said, here’s my question. If somebody reads this book, are they likely to tell a friend to pick it up? And he said, yeah. Because I’ve always heard that’s how books sell. So, it’s been very enjoyable. I don’t have any illusions that I’m going to sell a billion copies. The publisher asked, what’s your goal? I said I’d like to sell more than the Bible, but just the Old Testament. I have no idea if it sells three books or 200,000. But it’s been fun.

Andy: What’s in the book that’s going to surprise people?

Jeff: There will be some stories about NextRadio that will make people laugh and shock them. I think a lot of people will say, Holy shit! I sort of suspected that, but now I know it. Hopefully, the thing that will surprise people is there are a lot of funny stories about the stuff we’ve done.

Rick: I think that’s the theme that will emerge. I don’t know if it will surprise people, but I think it will delight people. Through the successes and failures, some great stories are told. That’s the key to anything, right? Whether it’s a book or a podcast, or a morning show. If you tell good stories, people will consume them.

Jeff: The other thing that will surprise people, I hope, is I think it provides an easily distillable analysis of the economics of sports, radio, TV, streaming, and podcasting that somebody could say, I never knew that. My editor said that when I went through the economics of streaming and podcasting and how sports evolved, she was blown away.

Andy: Let’s talk about the things that Emmis is doing now. And I’m not sure I know all that Emmis is doing now or which ones are active.

Jeff: Emmis has harvested cash, so Emmis is sitting on some cash. It’s no secret we have an FM that we leased to Disney/ESPN that will come back in a couple of years, and it’s pretty clear we’ll sell that. We have one more AM in New York, we have some more land here (Indianapolis). We have money in the bank, and we have three active businesses. We have Rick’s podcast business, Sounds That Brands. We have a dynamic pricing business, Digonex, which we’re quite encouraged about. And then we have a sound masking business, Lencore. Those are the three businesses. We’re looking for other things. We’re also involved like every other American in a SPAC. We may be in the final stages of something, but who knows? Those are the four active things we’re doing right now, Andy.

Andy: Do you want to elaborate on any of them?

Jeff: We like those businesses because we think there are good growth characteristics. Our job is to make them grow. We like what we see. It’s too early to tell whether any of them will be just smashing successes, but we certainly see some interesting trends there that are encouraging.

Andy: I want to come back and follow up on podcasting. You mentioned that nobody has made money, or at least broadcasters have not made money off of podcasting or streaming.

Jeff: I used to joke every time I spoke about NextRadio and streaming. My best example was what I used to say about Power 106. Our distribution cost was $60,000 a year. That was the cost of electricity to power the transmitter in L.A. For $60,000 a year, I could reach one person or 15 million people in Southern California. But if I took my transmitter down and I had to reach my audience, which is about 3 million people a week, it would cost me, and now this is outdated; it would cost me about one million dollars a year in data charges plus music licensing. And my listeners would also have to pay about $1M aggregate in data. The net result was probably $2M of total aggregate costs to reach the same people. The exact same people, with the exact same content. It’s why Pat Walsh used to say every time I take a listener from over the air to streaming, I take a 35% margin customer and make him a minus ten customer, or I lose ten percent for the exact same content to the exact same listener. Data charges are bundled now. But make no mistake, there are data costs and music licensing. It’s why, frankly, if you look at Spotify – one of our statements at Emmis is we ought to take $20 million and short Spotify. We said with our luck, the minute we shorted Spotify, Alibaba or Tencent would buy it for $100 billion, and we’d be wiped out. The reality is if you are iHeart or you are Spotify, and you rely on the economics of streaming, the math is impossible. And Apple being Apple has made it more impossible because they basically went to the music business and said, we’ll pay you $0.73 on the dollar. So Spotify at $0.65 on the dollar isn’t going to get much lower rates. The problem with that is you show me a business where 73% goes to music licensing besides all the other costs, and you make no money. Am I making any sense?

Andy: Are any of these big companies making money off of streaming?

Jeff: I don’t think so. Spotify will say one quarter, they’ll make a little, but I don’t believe that anybody has consistently made any money. By the way, that’s why Spotify went into podcasting. They said we can’t make any money paying $0.65 on the dollar for music licensing, so we’ve got to go buy podcasts.

Rick: There was a headline story, I think it was in Bloomberg, recently. The headline was something to the effect that Spotify’s $1 billion bet on podcasting has yet to show results, and investors are getting impatient. It’s logical that they moved in that direction because they needed something other than their high streaming costs. They needed content they could actually own. It made sense for them to do it. This article basically said the bet hasn’t paid off yet. Maybe it will.

Jeff: If you can get enough subscribers. The same thing is true with video. Netflix had a $250 billion valuation based on the idea that this thing will be wildly profitable. But when Netflix has a $21 billion gross and $19 billion in content costs, it is very, very tough. Even Disney, with its massive library, was projecting $5 billion of losses before they ever got to profitability on Disney Plus. It’s just really tough math, Andy. All this has transferred billions of dollars in value from distributors to consumers.

Andy: Please explain that, Jeff.

Jeff: Well, when Spotify can charge you $9.95, or I think for the version with commercials is free, and there are two or three units an hour, that is a bargain. It’s a great bargain for the consumer. But nobody’s proven that the distributor can make any money on that business.

Andy: Something has to give. Doesn’t it?

Jeff: Yeah, it does. You saw it give with Netflix losing 40% of its value. What happens is the bubble bursts. Wall Street loves what Wall Street loves, and all these things are based on “This is the Future.” This is the wave; streaming is the wave; podcasting is the wave. Then people start to look and say, you know, they’ve been doing this for ten years, and nobody’s making any money.

Rick: I think subscriptions are an elegant solution. But there’s a story every week or two about how consumers are oversubscribed and starting to lose their patience and cut back on things.

Jeff: A year ago, we talked about the brave new world of video streaming, and you had Paramount Plus, Disney Plus, Netflix, Hulu, Discovery Plus, and Peacock. The problem is all of them are saddled with massive content costs. We are seeing the same thing in sports, Andy. The first experiment is people cutting the bundles. I haven’t gotten into sports, but one anecdote sums up the entire sports business. You’ve got an 85-year-old grandmother in Pasadena who is a cable subscriber. She’s got a $100-a-month cable bill. She’s paying $10 a month for ESPN, $6 a month for the Dodgers, $4 a month for the Lakers and the Angels, $3 a month for the Kings and the Ducks and $1 for the PAC 12 Network. She’s got basically over $30 in subscriptions to sports that she’s paying as part of her cable bundle. She doesn’t know the Dodgers left Brooklyn.

The reality is all of sports in America are built on that bundle. But the idea is that sports get 100% of the consumers to pay for what 30% care about. As that bundle breaks apart with cable-nevers or cord-cutters, then that market for sports starts to decline. The best example is ESPN. At its peak, ESPN had 105 million homes paying $10 monthly for ESPN. Today, it’s 75 million homes. Well, if you want to look at ESPN’s challenges, you lose 30 million a month at ten bucks a month, and you’ve got challenges. Now the regional sports networks are saying if I used to have a million subs for Detroit Tigers baseball at $5 a month. Now I’m down to 750,000 subscribers. How do I make it up? They’re trying to go direct with streaming services. But the problem is to make the math work out, they have to charge people $20 a month. The Red Sox were the first ones. They’re charging people $30 a month. Even if you’re the world’s biggest Red Sox fan, you ain’t dying to pay 30 bucks a month.

Rick: The problem is this unbundling and cord-cutting is growing. At the same time, competition and fragmentation are increasing.

Jeff: The churn rate on all this stuff is staggering. The joke was when HBO got done with one of its series, it lost 30% of its customers. So you’ve got to hook them with something else.

Andy: That happens every time HBO loses a hit going way back. They keep having to crank out a hit before they end a hit or they’re in trouble.

Jeff: The problem is it’s very expensive, and it’s very tough to know what will be a hit.

Rick: I’m sure there have been a lot of conversations at Netflix over the past year. Oh, my God, where’s our next “Squid Games” coming from?

Andy: You’re right. They don’t know what will be a hit because I don’t think anybody there really thought “Squid Games” would become a cultural phenomenon.

Rick: Right. Absolutely. That’s right.

Jeff: The problem is they are just throwing enough stuff against the wall to try to create something that works.

Andy: For sure. Let’s come back to radio with the benefit of hindsight. Let’s create two columns. What did the industry get wrong or should have done differently? And what would you have done differently with Emmis?

Rick: I’m not sure the industry did anything wrong other than consolidation caused people to overpay from the traditional ten to 20 plus times (cash flow). To fund that, they increased spot loads from a traditional eight minutes an hour to 12, 15,16, and up.

Andy: Who’s still running only 12?

Rick: Exactly. I remember the intense debate we had inside Emmis when we decided that KSHE could go from eight minutes an hour to nine. It was a knockdown, drag-out discussion. A year later, we were all running 12. I think we hastened the fate of the industry with these oppressive spot loads. Personally, the more I’ve gotten away from radio. I put K-Earth (KRTH-FM/L.A.) on in the car the other day, not to pick on anybody. That is a magnificently programmed radio station. But the spot load is so oppressive it’s almost unlistenable. It is hard to listen to, and you see that more clearly when you’re not down in it every day. I think most consumers have seen that. I think that’s why people under the age of 40, people who have tethered cars, and people who no longer have clock radios have all moved on, and they’re increasingly moving on. You see it in the PUMM levels. Year after year, it drops another seven or eight percent. Those are people who have a choice. Every time we have another wave of new cars and more people have a choice, listening levels go down. I don’t know that there is a way to fix that. I really don’t. That’s why I increasingly think radio’s hope is a move towards spoken word and personalities that are unique and cannot be delivered by Spotify. The music delivery system is rapidly going away.

Jeff: I would add that companies grew and grew and grew. It was sort of a shell game. At the end of the day, the survivors had so much debt. iHeart had $20 billion of debt when the music stopped, and they never paid off any of it for ten years. Then they went bankrupt. They have so much debt. The only thing you do when you have massive debt levels in an industry that’s not growing is say, how do I cut my costs? Well, by cutting out all my disc jockeys or cutting out sales commissions or cutting production or centralizing everything, or cutting my real estate footprint. The problem is the more they cut; the less compelling they make the product to the consumer. You get back to what Rick said. There’s nothing local. There’s nothing compelling. The personalities are pretty much watered down or eliminated. Consolidation clearly led to excesses that the industry has never been able to escape.

Rick: By the way, if none of that had happened, I think radio would still be challenged because technology has come along and offered a better mousetrap. Let’s be blunt here: When you talk to a 20-year-old kid, and she says, I find my music on TikTok, and I have my own playlist. What do I need you guys for? Consolidation or not, that’s a really tough hurdle.

Andy: Is there anything you can say now that you couldn’t say in the past?

Jeff: Not really. We voted with our feet over the last five years. We loved it, but we felt that it wasn’t growing, and it wasn’t fun. I don’t think it was a surprise to anybody that we sold Indianapolis. Maybe it was to some people. It’s hard to be gone, but it was harder to stay.

Rick: That’s a good summation. Yeah, really hard, really hard to be gone, but even harder to stay.

Andy: Now I’m going to do stuff I save for the end. Instead of asking open-ended questions, I’m going to state opinions and then ask you to respond. I think radio, the industry royally screwed up because all the things about technology that you talk about. I think that radio should have done. We had the distribution. We had the knowledge. We had the audience. We had the brands. And we gave it all away because when we did things digital, in most cases, we had the person driving the van also in charge of the Internet. We folded jobs into other jobs instead. Instead of saying this is something new, we need somebody who understands it, and they need to be dedicated to it, and all the things that allowed us to innovate were the first things we cut. I think the industry made every possible mistake it could have made, allowing little piddly companies with no people or people working out of their basements and garages to build the companies that radio should have made. And I think that’s why. We’re struggling to earn $0.30 on a dollar on digital instead of owning it.

Jeff: Well, again, and I think you’re right, Andy, but it all gets back to the overall dynamics where the business was challenged. Everybody was looking not to invest but to save money because they had to service the debt. All the investments weren’t made. There were no Skunkworks because they were just trying to keep the wolves away from the door.

Rick: I question whether people skilled at radio have ever understood digital and had the skill set to execute it. We had a very checkered experience trying to sell digital radio. Sellers never really grasped it, with an occasional rare exception. I think there’s a lot of truth on the programming and content side too. Twenty years in, I’m not convinced that the skill set was transferable. That doesn’t mean we didn’t have a few people who got it. But we had a hell of a lot of people who didn’t get it. I continue to wonder whether the people who have historically been in radio would have that skill. As Jeff pointed out, we certainly weren’t equipped to go out and say, we may not have that skill set, but let’s hire a bunch of people who do and let’s be prepared to lose a lot of money for several years until we can build a successful digital business. Maybe some companies are, maybe Hubbard.

Jeff: We spent an awful lot of money on Emmis digital. We made a lot of investments. The verdict is still out on how much value we created.

Andy: That’s an interesting point. I wonder what the consensus will be. Did we miss the boat, or did we really not have the people? I understand your point. At that time, there wasn’t the ability to go out and hire many new people and create a whole new digital company. Emmis did as good a job at digital as any broadcast company – maybe better. In the end, you concluded, Jeff, I think, as you said, you went from a 35% margin to a minus ten margin. Maybe that’s the real answer. Maybe, I’ve been too harsh in my judgment. Maybe it really couldn’t have been done, and it needed people who were pioneers to cross the Mississippi, cross the Grand Canyon, and go to the Wild West. It is a good point. It’s one of my major criticisms of the industry, and I may have it wrong.

Rick: I don’t think we know yet. Both viewpoints have some validity. Which one prevails remains to be seen. But the view the radio industry didn’t go far enough and invest enough to do enough R&D to be a leader in the digital world or for people steeped in radio for years in some cases, decades and decades simply didn’t have that skill set. I think both of those things are possible.

Jeff: If you look at the best success in digital, part of the problem is that the Monopoly rents in digital are swooped up by companies that were the Facebooks, Googles, Amazons, and Apples. The best examples of success in radio are people like Hubbard and Townsquare. To a greater extent, they are the boiler rooms, they became local resellers of that stuff. That was a nice little business, but that was not groundbreaking digital other than boiler room sellers repackaging and adding some things for local advertisers that, in a large sense, were a lot of the dollars that went to the Facebooks anyway.

Andy: One of the other things I’m critical of is that the iHeart and the Radio.com or the Audacy apps are horrible mistakes because they killed off the local brands. I understood it was an effort to chase Facebook and Google for national dollars. But Jeff, you, and Rick will have a far better concept than me. I feel it never allowed radio companies to compete with Google, Facebook, and other national brands for dollars but effectively killed or damaged these local brands that meant so much.

Jeff: Andy, I can say it with a little more fervor than that. I will even be somewhat sympathetic. When Bob Pittman got the job, I’m certain he said to himself, “I have got to create a brand that creates the cachet with the streaming business. Then I can spin it off for $15 billion and solve a $20 billion debt problem.” I will give him credit by thinking that’s what he did initially, but he turned the company upside down to create a national brand. He not only did that, but he set a template for every one of his shiny objects. Whether it was streaming, podcasting, or music festivals, where not only did he throw a lot of money against the wall, but he used inventory on his stations every hour, which made the core product more unlistenable. If you listen to an iHeart station, you know there’s at least one minute on streaming, one minute on podcasting, and one minute on music festivals. Now in some cases, you take 15 minutes an hour and make it 18 minutes an hour. The net result is a further derogation of your core product. It sends the message to the consumer; why do I even listen to this?

There’s a reason you’ve never seen an economic analysis other than, hey, we grossed $40 million in podcasting or $70 million in streaming. Still, you haven’t seen a breakdown of the profitability of those businesses in over a decade. When you look at the net result, you harm the core product. The national brand meant nothing other than it allowed you to rent a yacht at Cannes to entertain advertisers. It did give you the ability to sell massive amounts of advertising to some national advertisers. A one-stop or one size fits all. I think the net result never helped the economic performance at all. That’s why that company has never paid any of its debt down.

Andy: I appreciate that. What do you think it’s done to the value of the local brands in local markets?

Jeff: The problem with this is that we didn’t promote the brands. Forget about Pittman and iHeart. They clearly were playing a different game. None of us promoted the brands. Everybody cut back on marketing, and everybody said, I don’t have the money to spend on research, marketing, or anything else.

Consequently, the consumer fell out of love with the product and stopped discovering it because it wasn’t in front of them. Those are all the sides of a business that declined. When was the last time you turned on the (local) news and saw an ad for a radio station? All of us are to blame for that.

Andy: If you’re king for a day, what would you do as it applies to the business? What are you going to change?

Jeff: If I could, I would change two things. I would change spot loads. The problem is everyone in the industry has a lot of debt. Let’s assume I didn’t have any debt. I would change spot loads, localize the personalities, and try to create compelling local content and market the thing.

Rick: My answer would be the same. That assumes that we have the ability to cut spot loads. Okay, we don’t have any debt. We’ve cut our spot load down by at least a third, if not by half. And we’re investing in developing personalities, which we’re pretty good at doing. We’re doing a ton of research and marketing the hell out of those personalities. We’re moving our radio stations away from just a music delivery vehicle and much more into the unique content that personalities can provide.

Andy: What are the odds that Emmis would return to radio?

Rick: Not good.

Jeff: Andy, my favorite saying in life is never say never. It’s hard to say this, but I don’t think that’s in the cards. Number one, you’re dealing with a 75-year-old guy. So actuarially, it’s not likely. But I would never say never. We love it. We always will love it. Loving it from a distance is probably where we are.

Andy: Is there anything I haven’t asked that you want to make sure that you get in?

Jeff: You haven’t asked me about USC joining the Big Ten. You’re the only person that hasn’t asked me that in the last few months.

Andy: Well, I could keep going for hours, but I have taken so much of your time. I also want to make sure that I include that everything they say about Jeff Smulyan being a nice guy is true and then some.

Jeff: And I’ve learned one thing that changed my entire life; that Cummings didn’t have a job at WSMB. That is probably the most shocking fact (laughs).

Andy: Yeah, and you should get your money back.

Rick: I did that for 41 years, and then I fucked up.

Jeff: Literally, this is everything! I would never have gone after an unemployed guy in New Orleans. Thanks for bringing it back. You know what’s funny? All kidding aside, I really did, in my mind, think that you were at WSMB, but maybe I did know that you had left SMB. I know that either way, it was a bad radio station. In spite of that, we’ve stayed together for over 40 years, and we’ve laughed together every day in all of those years. That I know.

Rick: Yes, that is for sure.

Andy: I appreciate your time.

Jeff: This was fun, Andy. I enjoyed it. It was. It was great. Thank you.

Andy Bloom is president of Andy Bloom Communications. He specializes in media training and political communications. He has programmed legendary stations including WIP, WPHT and WYSP/Philadelphia, KLSX, Los Angeles and WCCO Minneapolis. He was Vice President Programming for Emmis International, Greater Media Inc. and Coleman Research. Andy also served as communications director for Rep. Michael R. Turner, R-Ohio. He can be reached by email at andy@andybloom.com or you can follow him on Twitter @AndyBloomCom.