Wrong by a mile, it turns out, Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that there are no second acts in American lives. It seemed the proper sentiment at the time. Fitzgerald was both participating in and observing the Roaring Twenties, a time of absurd decadence by the rich that foreshadowed the Great Depression, and perhaps everything looked and felt obvious, good or bad, rich or poor, thriving or suffering. I grant you, that’s pretty high-hatted talk considering our topic. But Pete Rose, as coarse, base and ground-level as any American sports figure in history, died Monday as absolute proof that our lives may have second acts, third acts, encores.

They can do all that and still feel unfinished. Rose’s life certainly did.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Rose died at age 83 without getting what he wanted. He wanted one thing in his post-playing years, and that was the Hall of Fame. Even though Pete’s presence is all over that building in Cooperstown, he doesn’t have a plaque.

Where the Hall conversation goes from here is unknown — Rose faced a “permanent” ban from baseball, so you’d imagine some reconsideration could occur — but it’s a less interesting one without Rose’s voice in it. He was at turns belligerent and begging about Cooperstown. He for years denied the gambling that cost him his banishment, right up to the moment that he needed to promote a book in which he admitted it.

Rose retired as and remains MLB’s all-time leader in hits, games played, at-bats, singles and outs. The 4,256 hits he compiled should stay up there for a while; the closest active player, Freddie Freeman, has barely half that many (2,267) and Freeman is already 15 seasons in and 34 years old.

But Pete undercut his indisputable greatness, and he knew he was doing it, walking the razor’s edge. It was incredible self-sabotage. In the time that Rose was both playing/managing and gambling, first on the horses and later on anything he could put a wager on, the one thing that everyone in baseball knew was that you couldn’t bet on baseball, period, full stop, no quarter given.

Rose knew it. It’s not like he didn’t know. In those days, when I was covering MLB every day, the warning against gambling was literally posted next to the entry/exit of every clubhouse in the league. It was the cardinal sin.

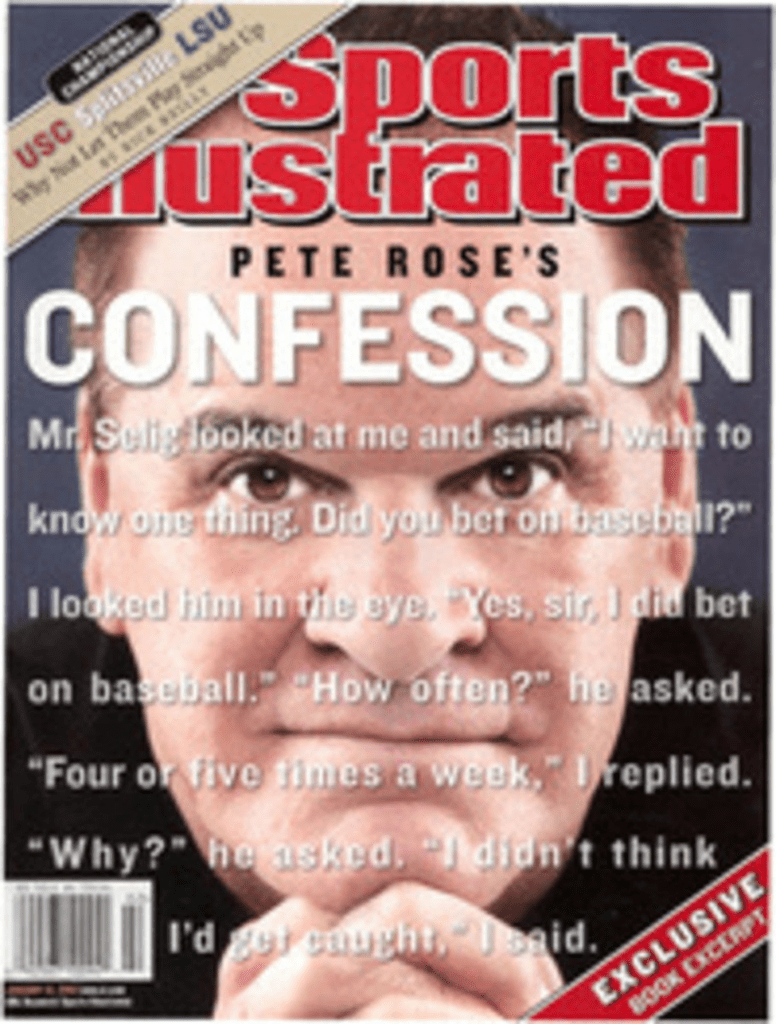

It’s amazing. There’s this Sports Illustrated cover featuring part of a conversation between Rose and Bud Selig, who was a couple of MLB commissioners removed from Rose’s banishment but still had the issue plopped in his lap on a regular basis:

Isn’t that all of it, right there? Selig asks Rose if he bet on baseball. Rose confirms that he did, yes sir, all the time. Selig asks why. Rose replies, “I didn’t think I’d get caught.”

It made for quite an SI cover. Of course, it was an excerpt from the book Rose was trying to sell at the time, in 2004. In a previous memoir, written 15 years earlier with one of the sport’s most esteemed scribes, Roger Kahn (“Boys of Summer,” etc.), Rose had vehemently proclaimed his innocence. But, you know, things change.

Pete later autographed copies of the mag, sold them at his memorabilia tables in malls and in Las Vegas and in the streets of little Cooperstown, usually within view of the Hall of Fame of which he was not a member.

Maybe you saw some of those autographed copies. They’d be sitting next to the baseballs that he would sign with his name and the inscription, “Sorry I bet on baseball.” (Currently available at your finer online used-merch sites.)

The show always went on.

The media never knew what to do with Pete Rose because he either was or wasn’t what they expected, depending on the day. I’ll tell you this, Rose was a writer’s dream. He always talked and never stopped, and in the instant that he said anything, you were convinced he meant every word of it. He spoke the way he played, bluntly.

Rose’s “Charlie Hustle” routine — remember, that name was bestowed upon him sarcastically, by veterans who quickly tired of the whole sprint-to-first-base-on-a-walk thing — did a weird dilution job on his actual talent, which was overwhelming. He was no average athlete who somehow got over with his scrappiness. Rose was a complete player, every bit as good as the numbers said he was. Journalists who initially understood him as a superstar MLB figure always had trouble squaring that with everything else that Rose was, or later became.

Tax evasion, documented womanizing, accusations of sleeping with an underage girl — there was a lot to the life of Rose. But once you’ve godded up a guy for decades, it can become difficult to find balance or bring things back to center. After the betting scandal led to Rose’s banishment in 1989, the media, much of it uncertain what to do (there were of course exceptions), essentially went hard the other direction: Rose as a devil and betrayer.

That’s not a first for journalism, but that latter portrayal stuck with Rose longer than he might have imagined. It’s fair to say that when he accepted his suspension by then-commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, Pete figured that “permanent” meant years, not decades. He was wrong.

Pete Rose was still grinding for his day in Cooperstown when he passed on Monday. In many ways, he died in some disbelief that for everything he did for baseball and meant to baseball, he could still be denied his place in the constellation of the sport. He knew the rules, just didn’t think they applied to him.

How the media will break on his legacy now is one of the fascinating bits of residue of the life of Rose. It was a very American life, size XL. As we all learned, those are hard to contain.

Mark Kreidler is a national award-winning writer whose work has appeared at ESPN, the New York Times, Washington Post, Time, Newsweek and dozens of other publications. He’s also a sports-talk veteran with stops in San Francisco and Sacramento, and the author of three books, including the bestselling “Four Days to Glory.” More of his writing can be found at https://markkreidler.substack.com. He is also reachable on Twitter @MarkKreidler.