The name conjures up an image of a television detective; Rick Dayton, NYPD. Maybe Dr. Rick Dayton on a soap opera. If there was a lab in Idaho that cloned cool names, ‘Rick Dayton’ would be the one donating the DNA. For radio or television, the name is a no-brainer. ‘Good evening Chicago, I’m Rick Dayton. And now sports, with Rick Dayton.’

“I applied for a job at a television station in Dayton, Ohio,” Dayton said. “We got to the end of the interview and the guy asked me, ‘Is Dayton your real name?’ I said, ‘No, it’s Cincinnati.’ I didn’t get the job.”

A woman walked up to Dayton in a Dairy Queen and told him he looked just like Rick Dayton. “I said, ‘I am Rick Dayton.’ She didn’t believe me and asked me to pull out my driver’s license. She looked at it and said, ‘That’s your real name?’”

I go to great lengths to write these pieces as snapshots of people’s lives. I don’t want them to be a regurgitation of a resume or a copy of a LinkedIn page. I want to reveal things about people you can’t find in a Google search. But look at what Rick Dayton has done. I’ll see you on the other side.

Rick Dayton; sports director at North Carolina News Network, covered the NFL’s Carolina Panthers, NBA’s Charlotte Hornets, NHL’s Carolina Hurricanes, NASCAR, statewide PGA Tour, Senior PGA Tour, LPGA Tour, University of North Carolina, Duke University, NC State University, Wake Forest University, East Carolina University. Dalton did play-by-play for men’s and women’s basketball and baseball for the University of North Carolina, N. C. State, Duke, and East Carolina. He was the syndicated program host and producer of DriveTime: The Golf Radio Show, Winston Cup Today, We’re Talking Sports with Rick Dayton.

Overachiever much?

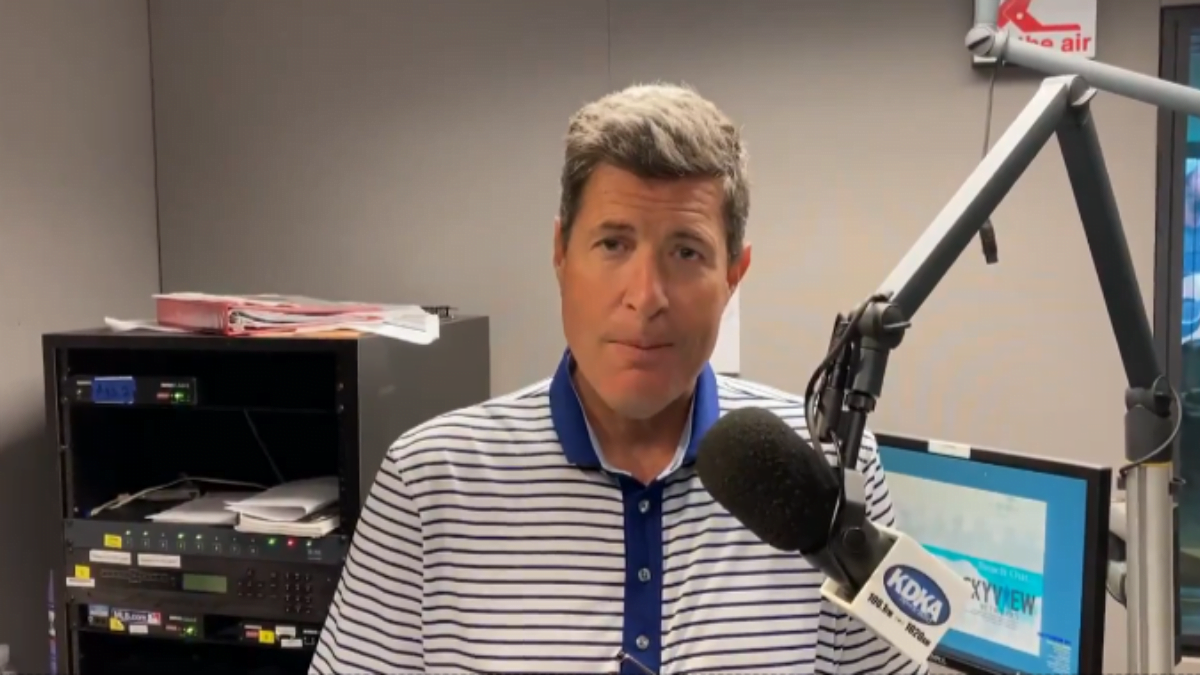

These days Monday through Friday 2-6 pm, you can listen to Rick Dayton on KDKA Newsradio.

Dayton started in radio as a kid when he was 15 years old. It was in Grove City, Pennsylvania, a 5,000-watt daytime station, WEDA.

“My speech teacher stopped me in the hall and said he thought I’d be good on the radio and invited me down to the station to see how it worked,” Dayton said. “He did a 7-10 shift on Saturday nights. It turns out I started doing that shift. I think largely because he was tired of being away from his family and wanted his Saturday nights back. I did that all through high school.”

Dayton anchored the news at the top of every hour, tore stories off the teletype machine, and wrote and read those stories on the air.

It was something he loved, and Dayton was working for great people and figured he might really do it for a living. He went to The College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. The town was known as the home of Rubbermaid and Smucker’s. One of the reasons Dayton chose Wooster was for the radio station it had on campus.

It was entirely student-run and programmed.

“Because I had three years of commercial radio experience when I walked onto campus, I pretty quickly rose through the ranks. In college I was majoring in speech, running the college radio station, acted as sports director, GM, did some underwriting for the station,” Dayton explained. He probably cleaned the windows too. “There were a couple of commercial stations in Wooster that did college games. I got to know those guys and they were very encouraging to me.”

There came a point in Dayton’s career where he reached a fork in the road. Yogi Berra would have told him to ‘take it.’

“I was doing sports on television,” Dayton began, “ when the GM at WRAL in Raleigh came up to me and asked if television was something I wanted to do for the long term. A career. A life. I told him I did. He said, ‘Rick if you really want to do this, get out of sports and get into news.’ He said everybody wanted to do sports. It was like being in a candy store. Covering all the big games was sexier than news. He said I can’t find good people to do news. If you switch, I guarantee you’ll never have trouble finding a job.”

At the time Dayton had three kids. A steady paycheck sounded good, so he moved to news. The writing was on the wall and the timing was right. He took a position as an anchor at a CBS affiliate in Huntington, West Virginia. He was promoted four times in three years and the main anchor for four years.

In television, you’ve got people writing a lot of your copy. Producers come up with a lot of the content.

“If I’m on at 4:30 am, there have been people writing that since the night before,” Dayton said. “I’m predominantly reading what they produce. I might rewrite some things to put it in my voice. There’s no script on the radio. You have to learn to formulate your thoughts. In that regard, it’s very different from television.”

Like in film, Dayton said television was a collaborative effort. He learned it’s just as easy to give back as take.

“When I had a camera person working with me, I didn’t know how to shoot video,” Dayton said. “I’d rely on the talents of the person behind the camera. In editing, I’d ask them what they felt the best shot was they got that day. Since I edited my own stuff, I could put it what I chose. I’d always make sure to get their favorite shot of the day in the package. Whether it was the sun coming up, a person on the bicycle. They loved that. With some reporters, their good stuff never made the package. They grew to learn if they worked with me, their stuff was in. It’s more interesting and people want to work with people who care about what they do.”

His job in television required him to do a lot of writing. If he had an amazing video in front of him in the editing bay, the last thing he wanted to do was screw it up with mediocre writing.

“Good video forces you to write better and tighter,” Dayton said. “I keep in my mind the story isn’t about me, not what I have to say. It’s about the people I’m talking to. They lived it, not what Rick Dayton thinks.”

Dayton said he may have the microphone and camera, but it’s the people he is talking to that know what has transpired.

Anchors and reporters tell hundreds of stories on television and radio. Many of them are of a routine variety. Then some stories change how you view your job and profession.

“I recall so many stories, but there’s one that will always stand out,” Dayton said. “It was the Sago Mine disaster in Sago, West Virginia in 2006.”

There was an explosion at the Sago Mine and it collapsed with 13 men trapped inside. They had been working two days to get them out, drilling down. As more time passed, they were running out of options.

“We were out there Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday,” Dayton explained. “By Thursday night they weren’t even sure they could get to them, even if they did get respirators to them. It didn’t look good and that’s what we reported on the 11 o’clock news.”

At 11:55 pm, CNN broke in and Anderson Cooper said there was news out of Sago. He reported while one of the miners had died, 12 had survived. This news came at the same time mining officials and the state’s governor cautioned against high hopes.

“People were dancing in the streets, singing Amazing Grace,” Dayton explained. “Their fathers and sons were alive. Everybody was absolutely ecstatic. We got all of it and went off the air at 1:30 am.”

Like a devastating tornado, the story violently switched directions.

“I’m back at my desk and I get a phone call,” Dayton said. “It was a woman who told me, ‘They got it all wrong.’ I asked her what she was talking about. She said we got it wrong about the mine. She said her husband worked for mine safety and the media got it wrong. Only one was alive and 12 were dead. I’m in the middle of the newsroom with this sinking feeling.”

At first blush, Dayton thought it was a crackpot calling. Some creep spreading a conspiracy theory for their own pleasure. But he had a feeling in his stomach he couldn’t shake. He picked up the phone and called station personnel still at the mine.

“I didn’t know this woman but I told our people to go back on the air,” Dayton said. “CNN was still there. What I wanted to know was why all the ambulances were still there. Why hadn’t the miners come out at that point? At 3:15 there was a press conference and we were told there was a horrible mistake. They confirmed exactly what the woman on the phone had told me.”

To this day when Dayton talks to high school and college students who aspire to be journalists, he uses this tragic story to emphasize accuracy in reporting.

“You cannot go with whatever everyone else seems to be saying,” Dayton said. “You need to step back and take a further look at the story until you’re certain. The newspapers went with it all over the country. I was there all night and did the morning show from the mine the next day. I’ve never been involved with another story directly that was so powerful, so poignant. We had mistaken information from seemingly authoritative sources. It’s not a good idea to outrace the truth.”

If he hadn’t gone into journalism, Dayton said he’d have been a college professor.

“At the same time I love learning something different every day,” he said. “I’m telling stories, informing people, educating people. Sometimes I have no idea which direction we’ll go. A lot of times I’ll hear people say they saw one of my stories and how much they may have enjoyed it. What they don’t see is the interview I did with someone who led to the story they saw. The one that led to that package. Crafted the story. Those are the critical people.”

He’s a naturally curious person who doesn’t like to script his interviews.

“I won’t tell people what I’m going to ask them about,” Dayton said. “It’s my second question that informs my third question. I will learn more about a person or a situation if I’m asking them questions as anybody else on the street would.”

Jim Cryns writes features for Barrett News Media. He has spent time in radio as a reporter for WTMJ, and has served as an author and former writer for the Milwaukee Brewers. To touch base or pick up a copy of his new book: Talk To Me – Profiles on News Talkers and Media Leaders From Top 50 Markets, log on to Amazon or shoot Jim an email at jimcryns3_zhd@indeedemail.com.